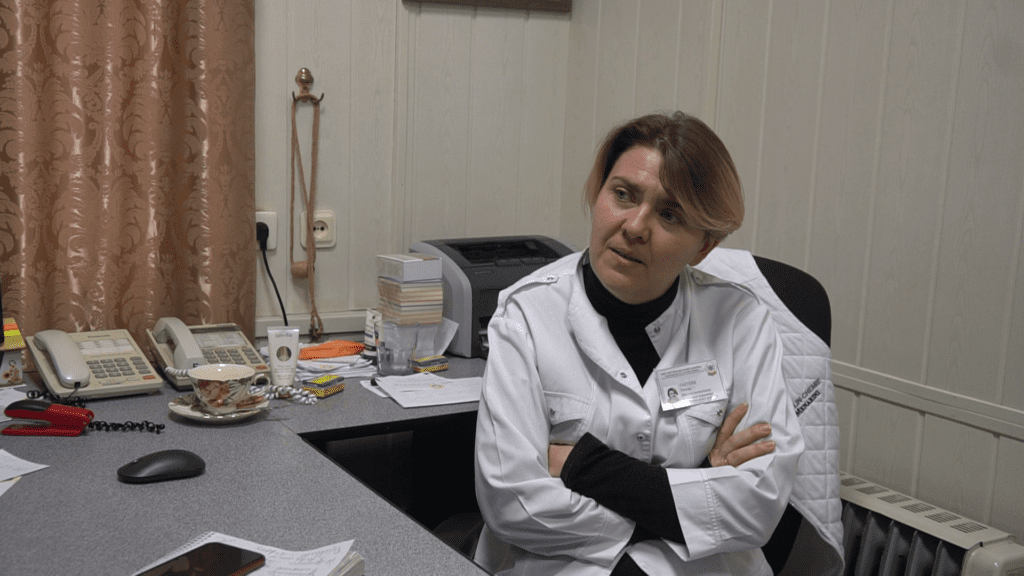

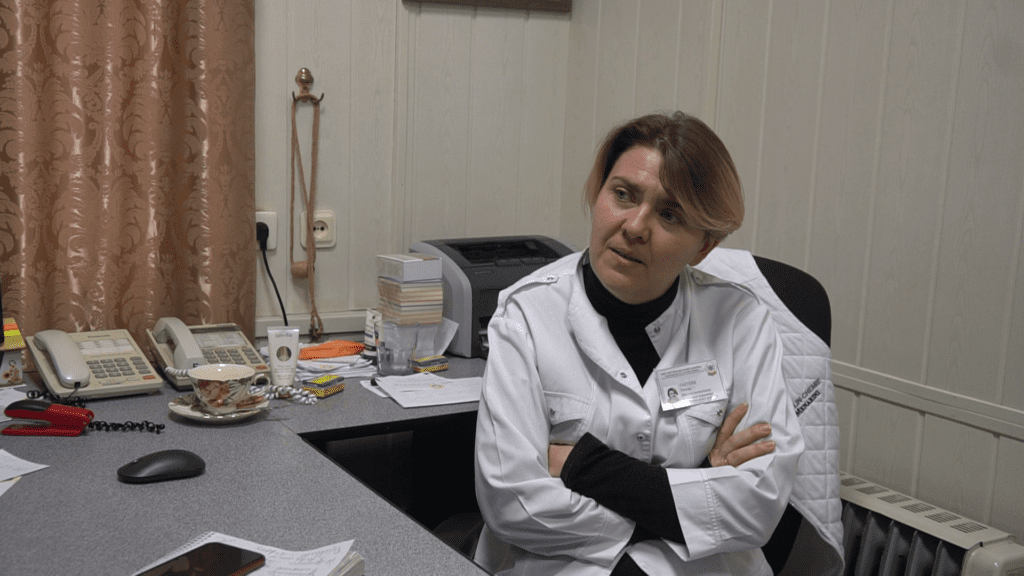

Freedom under missiles is still better than living in fear

The liberation of Kherson came at a price. Upon their withdrawal from the port city in southern Ukraine, the Russian invaders cut Kherson off from public services depriving the tens of thousands of residents of electricity, heating and running water. Free as it is, the city now faces ever-increasing artillery strikes from the other, still-occupied side of the River Dnipro. Still, many say it is better than living under occupation. Anna Hosmeva, director of the Kherson Central Hospital, one of the beneficiary institutions of generators procured by Hungarian Interchurch Aid (HIA) in its latest response to alleviating the difficulties in Kherson, agrees. HIA spoke to her about her experience of the occupation and its aftermath and how freedom can only be enjoyed when the most basic needs are met.

HIA: What are the biggest problems in the institution at the moment?

Anna Hosmeva: One of the biggest problems is the lack of electricity. We aim to address this by procuring generators, such as the ones delivered by HIA to ensure that all departments can function smoothly. Although we now get our power from the central grid, in the current situation there could be a power cut at any time, so generators are essential to ensure that we can continue our work in all circumstances.

What do you mean by “current situation”?

Look, the hospital used to have over 1100 employees. Now, if I count all departments, there are just over 600. Some of the staff left during the occupation, although it was much more complicated then, with Russian checkpoints swarming and, in many cases having to go through the so-called ‘filtration camps’ of the Russian secret service. And by the current situation, I mean the constant artillery attacks. Understandably, some are afraid to return to the city, and some are afraid to stay.

Are you not afraid?

My husband is also a doctor, so we stayed during the occupation to continue doing our job. We made a lot of “jokes” about being stuck in the city of “pets and the elderly”. But to be serious, most of the elderly either had no means of leaving during the occupation or nowhere to go. And what do many elderly people need regardless of the war? Medicine. Many visited the hospitals because if a medicine cost 300 hryvnias (about USD 8) before the occupation, its price rose to 3,000 hryvnias (USD 80) under Russian rule. We tried to supply everyone from our reserves and provide them with the medicines they needed.

And at the end of the occupation, many people came to stay a few days at the hospital because they had no electricity, running water or food at home. Here, at least, there was some comfort for those who, because of their age, for example, could not get water and food on their own. Also, the lack of heating drove them to find a safe haven.

So, you had electricity and water supply to the hospital even after the withdrawal of the Russian forces?

No, nothing for 23 days. After the occupation, water was provided by the emergency services, volunteers and often by the hospital staff itself, so we had no shortage of it. With no electricity, we worked with battery-powered lamps or anything that could be used for lighting.

Kherson was cut off from utility services just as winter was beginning. Did the lack of heating cause a spike in cases related to the cold?

This is the time of year when the number of such health problems usually rises. I can’t give you statistics because people are coming and going, but the fact is that in many places, especially in multi-storey houses, the lack of central heating is a serious problem. These buildings are not the best insulators, so to speak.

It is said that many people try to heat their homes with gas ovens. Is this not dangerous?

Of course, it is dangerous. We’ve had a few patients come in with gas poisoning. But unfortunately, that’s what happens when people are cold.

You hear a lot about how during the occupation, a lot of people were arbitrarily arrested, detained for days, and in many cases, tortured. Were the more fortunate ones who were released able to have their physical injuries treated here? Was there an example of this?

The first thing to understand is that we lived in fear for eight months. Those who came in with injuries did not even want to give us their identity documents. And they refused to say where and what had happened to them. You see, until the outbreak of the war, it was the doctor’s duty to collect this information to provide effective treatment. During the occupation, that changed, and we treated everybody as best we could, without question, so to speak. People were afraid to talk about what had happened to them. They were afraid of reprisal.

Unfortunately, what you mentioned, the arrests and going missing happened to several of my colleagues. They do not want to talk about it either.

For eight months, we lived from checkpoint to checkpoint, fearing that we would come home to a search warrant or worse. We lived by precautions because the priority for everyone was survival.

What precautions?

The invaders actively searched for “suspicious elements”. The most common way of doing this was to take the phone and check its contents from end to end. The slightest sign of supporting Ukraine could be a reason for arrest. I, for example, had two phones. I used one to go to work and the other, the “real” one I kept hidden at home.

In my opinion, we still have to come to our senses to be able to come to terms with what happened. It will take time, but currently that is a luxury. You see, this building we are in was the Covid department for two years before the war. By the time the epidemic had calmed down, the war had broken out, and then, after eight months of occupation, we were cut off from utility services for almost a month. Now we are under fire. Whether we like it or not, fear has become part of our lives.

And now, how do you feel about the deteriorating security situation?

Look, life is happier than it was. For those who have not been here, it is hard to understand that explosions are not nearly as scary as being under occupation. After all, for eight months here, we listened to the bombing of Mykolaiv.

We are free now. If you want to, you can get in a car or on a train and leave. No one promised us that things would improve, but from the many terrible things I have heard, we can still count ourselves lucky. There are places where the elderly simply did not live to see this “pseudo-border” moving. That is just horrible.

I remember when the first grocery store opened after the occupation. I went in, and I shuddered. “What, you can pay by card? The shelves are not empty?” I have been going there for “weekend trips” ever since.

You know, for eight months, we went to markets where we could only pay by cash for goods getting more and more expensive with each passing day, but we also bartered. I still remember the nineties (the economic crisis in the former member states after the collapse of the Soviet Union – ed.). Still, even those years were bearable compared to the occupation.

Is it safe to say that you are relieved to see the end of the occupation, despite all difficulties?

Many things during the eight months made our work difficult. One of these was, once again, fear. But not fear of the Russians but of being abandoned by our own. And I could go on and on about how many cities across the country are experiencing difficulties. Kharkiv, Kyiv, Mykolaiv… But these are free cities, as is Kherson.

Meanwhile, people are still under occupation on the other side of the Dnipro. We can’t contact them, we don’t know what’s happening to them. What has been happening to us for eight months is probably still happening to them.

Look, the difficulties here are manageable. We have electricity and water. You really appreciate the small things when you don’t have them. Of course, there are little inconveniences you don’t think about in peacetime. For example, having drinking water at home. At the end of the working day, there are queues at the distribution points for two or three hours; if you want fresh drinking water at home, you have to wait your turn. But it’s not as bad as it sounds. The shooting is worse.

Many civilians who lived through the horrors of war have adopted a fatalistic attitude. “It’s all written above,” they say. What do you think of this in view of the increasing artillery attacks?

It is not for nothing that I said that the worst part is the artillery strikes. You can’t do anything about them; you have no power over them. I am reminded of a saying: ‘The trenches are where the Good Lord is most often spoken of’. I suppose that’s true. But I wouldn’t say I’m a fatalist because if it’s written and everyone is on their way to their graves anyway, why bother helping people? A colleague of mine, who has lived through severe difficulties, used to say: ‘of two duelling samurai, the one with the greater spiritual strength wins the fight’.

If everyone does their job honestly and to the best of their ability, they will face fewer difficulties. That is what I think. We, too, here in the hospital, will continue doing our job, doing what we are good at. Not because we have to but because we want to. Out of our own free choice.

Hungarian Interchurch Aid was among the first international aid organisations to help refugees and people in need both in Ukraine and Hungary. HIA has been present in Ukraine for 25 years – since war broke out, it has helped more than 200 thousand people in 19 regions of Ukraine, delivering close to 1,500 tonnes of aid to the war-torn country. HIA’s humanitarian programme is implemented in collaboration with ACT Alliance, providing emergency aid as well as cash assistance and psychosocial support to those in need. Kherson, where this conversation took place already received two major shipments of food, sanitary products and power generators in November and December.