“We cannot leave those, who have been forsaken by everyone else”

Incoming news about life under Russian occupation in Ukraine are increasingly worrisome, civilians stranded in such territories speak of harsh living conditions, shortages and deprivation, as well as other difficulties. Against all odds, Olha Fomenko is trying to carry on with her humanitarian work in the Russian-occupied part of the Zaporizhzhia region of Southern Ukraine. She and her husband take care of people who, in her words, “have been abandoned even by their very own family”. The war, however, created such challenges that she cannot face them all alone, and although Damocles’ sword hangs over her, she perseveres. Olha lives from day to day, not knowing what tomorrow will bring. One thing she knows for sure: she will not leave those who can only count on her. Her struggles are supported by Hungarian Interchurch Aid.

“We are believers, providing shelter, food, and clothing for everyone who turns to us for help,” the middle-aged lady introduces herself at the far end of a failing telephone line. In Olha’s home in the village of Blahovischenko, just like in most of the occupied areas, it is not far from a miracle to have a proper telephone connection to the “outside world,” that is, to Ukrainian-controlled areas.

While the phone line was loud and clear, one could tell right away by Olha’s delicate but noticeably disturbed voice that she was not exaggerating, her situation is grim. Explosions constantly rock the sky, shockwaves shake the ground, and “when you go to bed, you never know if you’ll wake the next morning,” she says.

The line was disconnected after two minutes, so we continued our conversation with Olha in short, concise chat messages.

Her description of the situation in her settlement was anything but cheerful. Rockets and other projectiles rain down over the town all day, which has already become a regular part of everyday life. Water and electricity supply is gone, and after many weeks of outages, basic amenities seem to be a thing of the long-forgotten past.

Even if Olha wanted to, she could not leave the occupied territories because, according to her, she would need to pay a “fee” to enter the Ukrainian-controlled territory, or in other words, a bribe at Russian checkpoints. But she is unwilling to escape the occupation, for she and her husband have people to take care of.

“We can’t leave behind those that everyone else has given up on,” Olha explains, adding that “these people have been abandoned even by their very own families.”

Even the smallest help can save lives

“All the seeds and wheat have already been taken out of our village,” says Olha, pointing out that they can’t even cope with the general food shortage by growing and making their own food. That is why “we chew on a tiny piece of bread every day,” she adds.

Olha received a small but life-saving aid delivery from one of the members of ACT Alliance. Hungarian Interchurch Aid (HIA) through a volunteer of its partner organization, the Zaporizhzhia-based Santis as soon as they received Olha’s plea for help. The aid consignment should ensure the survival of her and the eight people in her care for another month.

Although Olha says there is a shortage of everything in Blahovischenka, most of her woes are rooted in financial problems caused by the occupation.

Does money buy happiness?

Olha spoke of heavy Russification, a term used to describe the efforts of the Russian Federation to forcefully integrate occupied territories into its own legal and economic framework. The Russian ruble has replaced the Ukrainian hryvnia, and Russian goods fill the shelves of shops. The Ukrainian currency, which was virtually rendered useless by the occupiers can be exchanged for the Russian money in banks, but alas, “when you have got no money, you’re left to fend for yourself,” Olha explains.

“We won’t get any financial help from the Russians, even though we can only buy food with their money,” she continues.

Money can be earned through work, but jobs are hard to come by nowadays. Even if the job market was booming in her home village, Olha and those in her care suffer from health problems that make it impossible for them to work. Thus, the problems Olha and the remaining people in Blahovischenka face are all intertwined. With no work, there is no money, with no money, one cannot buy anything, neither food nor medicine.

“Three of them suffer from high blood pressure, one 40-year-old woman will go blind without surgery, another has a broken leg, yet another has to endure epileptic seizures. In the meantime, I have a neck hernia that I’ve been suffering from for a year. I can’t sleep, I am in constant pain, and there’s nothing I can do about it,” Olha says, describing their frustrating situation.

To make matters worse, the medical supplies in Olha’s village are not just lacking, but the pharmaceuticals that have appeared in the local pharmacies brought in by the Russian occupating forces are expensive for empty wallets. Even if Olha had the money to alleviate the pain she and her people suffer from, their problems supersede the effects of any medicine. They need professional medical attention, but Olha says all general practitioners have left the area, so they can’t even get a check-up, much less a referral to a hospital. Also, money is required for hospital care, and as she said, they are short on that.

“Medical care costs money, buying food costs money, repairing the roof so that the rainwater doesn’t drip through the ceiling costs money. Everything costs money,” she cries as she sends pictures of her truly dismal living conditions.

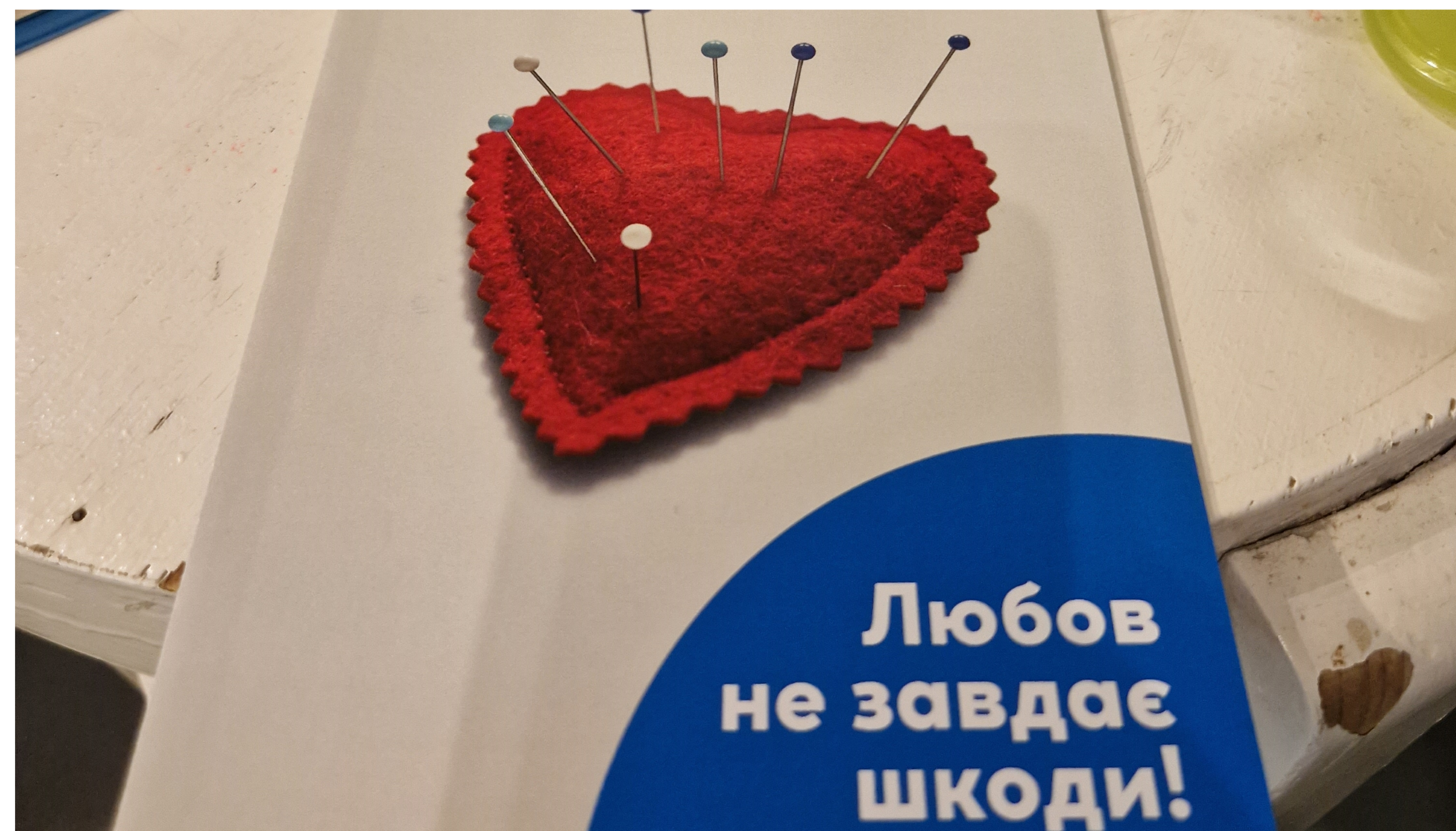

Despite all hardship, her faith seems to remain adamant. I ask her whether she’s got any plans for the near future. Her reply was so fast, that it was obvious she didn’t need time to think of the answer: “Not much, we are not in the situation to make plans. We ask God to help us, and I think He does. I mean, our plea reached you and the help we desperately needed did arrive” she says gratefully.

But reading between the lines of her messages of gratitude, her words radiate despair. I ask if there is anyone apart from HIA’s partner organization she and her people can count on. “God,” comes the Olha’s brief reply.